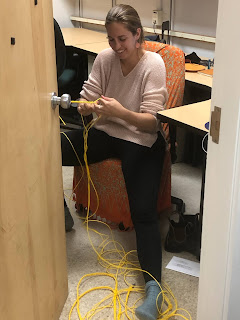

Rumpelstiltskin

My grad student, Kharis, braiding rope for a bridle to deploy equipment in the ocean. "You know, if you had a male grad student, they would not know how to do this," my grad student observed smugly. She was draped in yellow rope, braiding with her hands and keeping the strands from tangling with her feet. She looked like Rumpelstiltskin spinning straw into gold. I smiled and shook my head. She was right - that level of scientific arts and crafts was distinctly female. In another corner of the lab, I had my own straw-based alchemy experiment going on. CATAIN 's electronic entrails were sprawled out on the bench top, with cords of every imaginable kind attached to ports in the camera's Raspberry Pi computer. There was HDMI, ethernet, USB, a small white jumper, a 6-prong connector with 3 of the prongs purposefully removed, and little hook-shaped terminals that were way too delicate for my liking. If I may continue the Rumpelstiltskin metaphor, I was the princess, sitt