The nuptial dance of the nereids: part 2

|

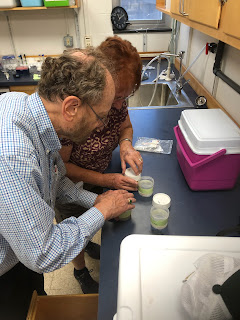

| Jeff and Michal hard at work in my lab, preparing worms for an experiment. |

That's right, my worm-obsessed summer guests are back in Woods Hole! Jeff wrote to me earlier this year to ask if it was ok for him and his wife to use my lab again for a week while they ran experiments on spawning polychaete worms. They were such excellent guests, I was happy to host them again.

Jeff's target species is Nereis succinea, a wiggly segmented worm that swims to the surface on dark nights around the new moon. The females spin in circles while releasing pheromones, and the males are stimulated by the pheromones to spawn. It's super fascinating to watch - the response is nearly instantaneous. Normally, a male worm will swim laps around the perimeter of the dish he's in, but if you add just one drop of the pheromone, he immediately changes course and fills the dish with sperm. A single male can spawn up to 40 times, so you can use the same individual for multiple trials if you rinse him off in between.

One thing I wanted to do this summer was have Jeff give a talk on his research to our larval ecology lab group. Several labs at WHOI get together each week to discuss recent research, share our own work, and get feedback from the group. We used the regular meeting this week for Jeff to explain what he's working on and why it's important. You see, the pheromone that Nereis uses as a spawning cue is not just found in worms. The pheromone - or rather, various oxidized versions of it - are also found in humans. If I may quote one of the slides from Jeff's talk, "What is a worm sex chemical doing in my blood?"

|

| Nereis succinea. The worm in the background has released sperm into his dish, so the water is cloudy. Photo by Johanna Weston. |

Speaking of connections, there was a moment yesterday that absolutely blew my mind. Another summer visitor at WHOI, a neurobiologist named Tony, joined the larval group for Jeff's talk. As Tony gazed across the table, he asked, "Have we met before?" It took just a few minutes for Tony and Jeff to recall a conference on mollusk reproduction they had both attended in 1991. This launched an excellent discussion on invertebrate biology and the pathways that scientific careers can take. Friends, the world is small.

It has been such a pleasure hosting Jeff and Michal this week. I hope the experimental results turn out well, and I can't wait to see the paper that emerges from their work!

Comments

Post a Comment