Team Porites online

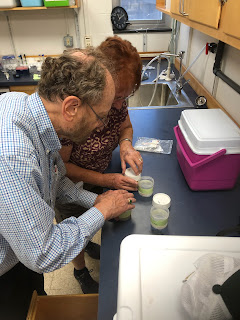

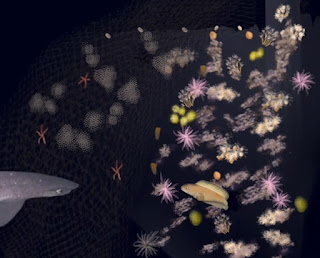

It's not every day that I pop out of bed and make it to work before 8 am, but yesterday, I was super motivated. I had an 8 am meeting with Team Porites . "Hang on, let me get a picture!" - Sarah Davies That's right, we got all of us online at the same time! It was 8 am in Massachusetts, 2 pm in Europe, and 9 pm in Palau - the only time that all of us could be reasonably expected to be awake and mentally functional. I'm so glad we were able to make it work. Since parting ways in Palau at the end of May , each member of the team has been working on their own set of samples and data. Matthew shared updates on the paper he's writing about spawning in Porites lobata , and I was super excited to hear about his progress. "The spawning paper," as we've started calling it, reports our observations of P. lobata spawning in Palau, describes the larval development , and lays the foundation for future studies on this common species. We even decided to inc